-

Gilmore is the Oldest Original Millennium Line Station

Gilmore at platform-level

If you were to pull up information about the Millennium Line, you’d soon come across its opening date of January 7th, 2002. With that known, you’d then say that every station opened then as being the oldest.

This assumption is fairly safe as the line itself is a relatively new railway. Unlike the Expo Line, much of the initial alignment did not make use of a another railway’s existing or former right of way. This means that stations such as Sperling-Burnaby Lake or Lougheed Town Centre have no real historical reference.

However, this is not entirely true for all of the stations which opened in 2002.

A view towards a right of way crossing at Gilmore and Henning

The BC Electric Railway used to run a similar line to compliment the Central Park line named the Burnaby Lake line. It ran from New Westminster at the same spot the Central Park line did and merged with the street car line on Commercial Drive just its sibling.

At some point, I should write about the Burnaby Lake line, but the point here is that the Millennium Line does intersect with the remnants of this line.

Gilmore station as viewed from the same spot

Today’s Gilmore Station is located at the intersection of the street bearing its name and Dawson. It’s probably one of the weirder stations in my opinion not because of anything other than its ceilings resembling curved plywood. I guess one can just go across the street to the Home Depot to pick up replacement panels should any of them fail.

However, the station’s previous incarnation was fairly unassuming and significantly more rural.

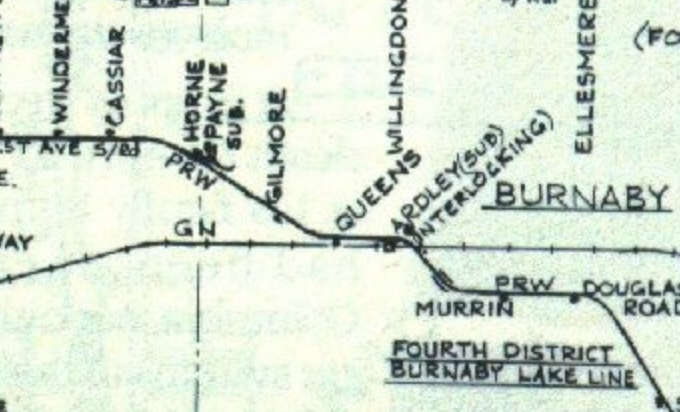

Map showing GIlmore on the Burnaby Lake line (City of Vancouver Archives)

The original Gilmore Station from the Burnaby Lake line days was too at Gilmore and Dawson. It was to serve the swampy, agricultural area known as Still Creek. I could write extensively about the history of Still Creek, but really that was just it.

As part of the shutdown of the BCER in favour of trolley and diesel buses, it closed in 1956.

Interurban travelling along the Burnaby Lake line (City of Burnaby Archives)

The main difference between the BCER station and the one we have today is where the current station stands. However, the original station site does continue serving a public good.

View of the Gilmore Pump Station approximately where the original Gilmore station stood

On the site of the original BCER station is Gilmore Pump Station, which while does not serve rail traffic anymore, it does serve a function to make sure that if you were to come downstairs from the Millennium Line, you don’t encounter a giant puddle.

This originally appeared on cohost.org/VancouverTransit but has been moved here due to the site’s shutdown.

-

SkyTrain and Industrial Control

This is a Twitter thread from July 2018 that I made into a blog entry.

I want to talk about how important industrial control is and why the general public is woefully unaware of how they interact with it on a daily basis.

This is a post on SkyTrain, Vancouver’s rapid transit system and how safe it is until users circumvent it.

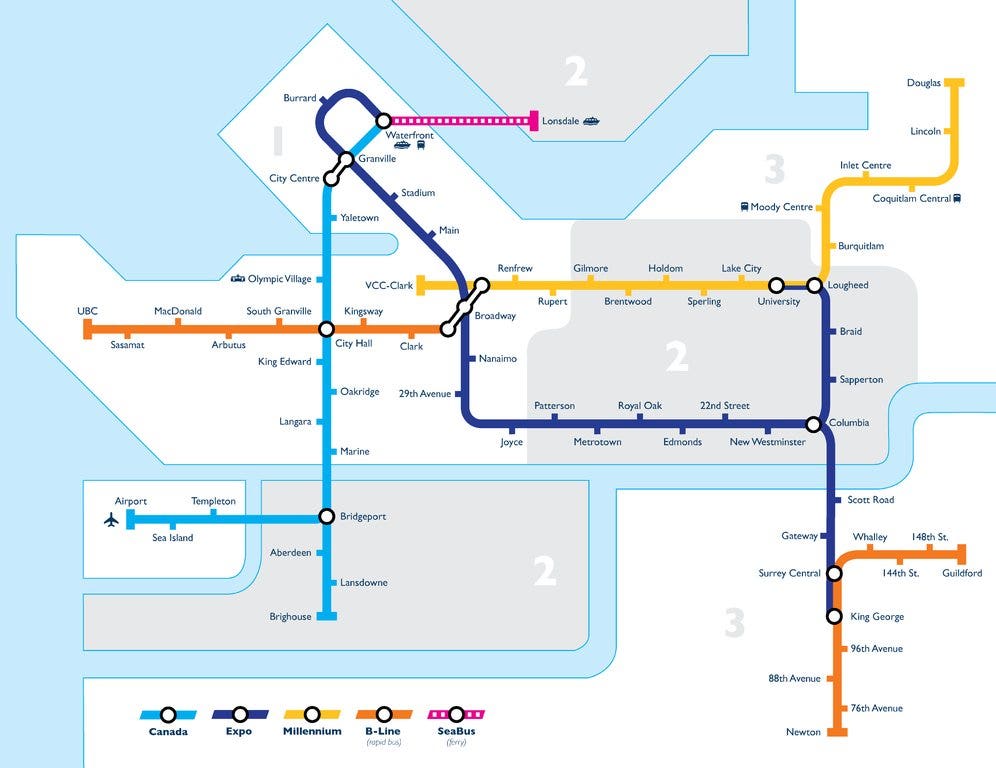

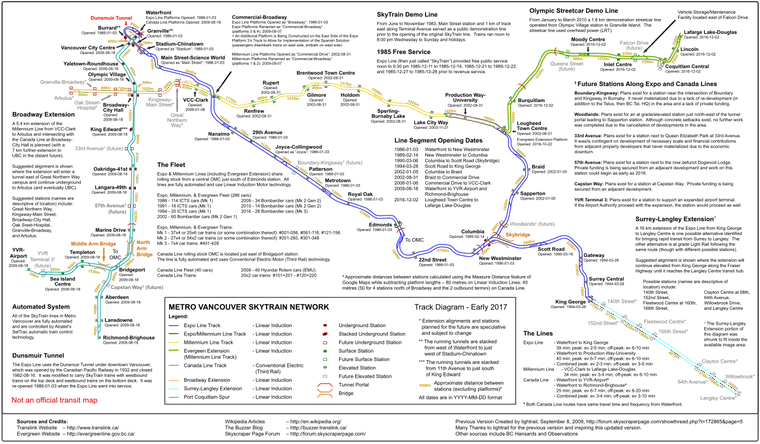

SkyTrain has just about 80 KM of track and it’s 100% automated. This means that when you walk on to any of the trains on any of the three lines, there is no driver. Because of this, it can achieve and has achieved 70 sec headings, meaning you don’t have to wait long for a train.

More often than not it’s about 120 sec but still few systems in the world can achieve this maximum frequency.

Its frequency is also its biggest Achilles heel when things go awry, but I’ll touch on that shortly.

For the very curious, the trains use the Seltrac moving block system. This allows for the trains to run very close together to the point where trains can actually be right in front of each other with a few metres to spare.

To prevent people from going into the tracks, there are various sensors at entry points where humans could interact with the trains. The trains don’t have anything to detect a human is in its path; it just knows where it is.

Or in some cases wildlife gets into the track. This is a new extension of the system and it’s not too far from an interface zone, allowing for cougars to enter. The line was not operating at the time.

So optimally, trains know where they are and humans never enter the track. Unfortunately, it does break from time to time…

(View talk on elevator security on YouTube)

The way I look at our rapid transit system is like this: it’s like an elevator. An elevator is designed to never kill you provided that you don’t circumvent the safety controls.

So what happens when humans circumvent the safety controls by opening doors when the trains are stopped? A lot of things and it messes up the balance of the system.

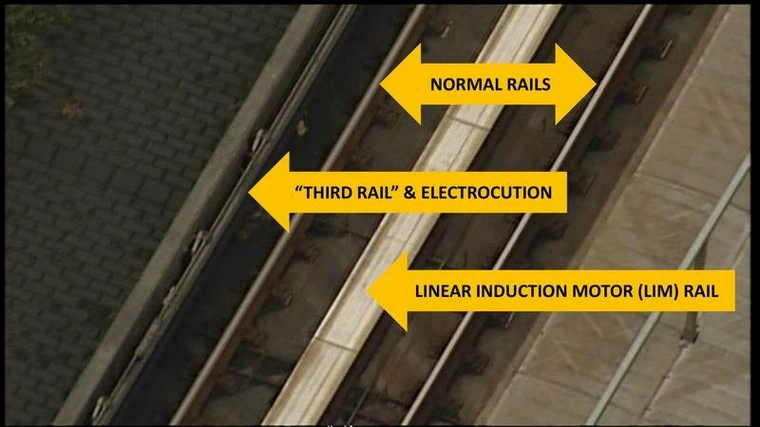

SkyTrain operates using a third-rail system, meaning that electricity is provided by a rail on either side of the track to feed electricity. It is very easy to end up touching it if you are unaware.

Also the trains operate at 80 KM/h at maximum speed.

All of this means that if someone exits a stopped train, everything starts to go hairy fast.

First off, SkyTrain has to have the section of track where people are thought to be walking through turned off and to stop all trains from approaching the stations between them. This means that a huge section of track going both ways is now disabled.

Secondly, attendants have to assist the riders who opted to leave the trains with getting on to the platforms. This has to be completed before we can do anything further. It may take an hour or more.

So here’s where the fun part comes in: what happens when you decide to knock out power to these trains? We lose the ability to trust their state.

That’s right. We’ve lost the trains and now the system has no idea where any of them are.

To bring the trains back to life we cannot just turn them on and tell them to go to the next station. They themselves do not know where they are and the system does not have the ability to make them trust their current position.

These self-driving trains however have to meet requirements every few months by having them driven by an operator. Almost all attendants are trained to operate the train when need be–due to weather or maintenance.

So to fix this: we have to have the train sets driven into their nearest station one set at a time. This is the longest part because there are sections of track that are nearly 3 KM long.

Once this is done and we’ve ensured that nobody is in harm’s way, we can have the system come back to life.

I’ve ridden this network every working day for the past decade and can [confidently] say that the system is very safe. However, the biggest problem it has is that when it breaks, people tend to get frustrated and cause the system to break further.

In 2017, the system recorded a record 151 mn passengers (compared to 117 mn in 2010) and on average the majority of system delays are caused by humans interacting with the trains either intentionally or unintentionally–I will not elaborate further.

(There is a train 069 BTW)

How this all ties into industrial control [(IC)] of course is that this is the very definition of one that the public uses every day and pays no attention to how it works. Often we talk about IC in power plants, natural resources, and elsewhere, but our mass transit systems are IC!

IC security is super important but it is also important to understand how much goes into making a good IC system work. It isn’t just having to worry about security matters but to also plan for humans interfering with the operations of things.

So the next time you’re stuck on a train, don’t break the emergency seal. It may be 15 minutes for you but you may cause 120 minutes for others.

I should add: I don’t work for TransLink! If I did I’d probably wouldn’t be allowed to [chost] about this stuff. I work for a company that heavily uses industrial control so as a result I have an interest in how things like SkyTrain works!

Fun fact: I was DM’d by two TransLink employees asking me if I worked for them when this thread started to make the rounds locally. I literally just transposed my knowledge of industrial control to how these trains work! Knowledge of industrial control equipment is just something I gained from my career and it isn’t hard for me to look at systems and figure out how they tick.

-

A Fool's Errand in Cyber Security and Beyond

One of the “holy grails” of cyber security is reducing all panes of glass used by incident responders to just one. This is a pipe dream many managers chase after in the name of efficiency and it is not unlikely to have reporting staff desire this too.

Despite all of this, I have long had the opinion that the single pane of glass concept is a fool’s errand and prefer to chase after reducing the windows used in incident response.

What is a “single pane of glass” anyway?

The “single pane of glass” (SPG) approach really is to reduce the complexity of performing tasks or absorbing information by making it solely available in one location only. This could be exemplified with a ticketing system which shows diagnostic data and have one-click tasks to handle basic functions.

Other examples that you may have seen include tools like Matrix and Hootsuite, which handle multiple online services.

As you can tell, it is not a cyber security problem entirely.

Interoperability is a nightmare

Here are typical tools I could expect to make cyber security incident responders successful:

- Endpoint detection and response software (EDR)

- Phishing email reporting

- Network firewalls and detection

- Logging software

- Sandboxing for malware detonation

This is just a small list of software but is something I’ve had to try and make play nice.

Here’s a fun scenario that I expect could easily play out:

Jonathan in office services reports a phishing email. When the email is reported, an incident responder determines that it was malicious and that the URL the email linked to had mimicked the corporate login for a service which didn’t have two-factor. Said website was harvesting usernames and passwords and then offered a download to access a service.

The incident responder then takes the URL and checks to see who clicked on it and three employees were recorded to have visited the website. Web traffic logs were fortunately able to capture activity and it was determined that one of them who is in the help desk did sign in and download the file.

Now the incident responder has to grab an audit log from the EDR to see if the file was executed and is also grabbing the file from the machine to then test in the sandbox environment. The responder has since isolated the machine to prevent any further harm.

At this point, we’ve gone through five different software products, meaning five different windows had to be used. The single pane of glass approach would break down these functions into steps:

- Review the maliciousness of the email

- Search logs from network firewall to see who visited the URL contained within

- Retrieve EDR audit log

- Review audit log for execution

- Detonate the malware in the sandbox

- Isolate the computer

These are six steps and in theory all of these steps could be done with integrations. However, this is where it all begins to fall apart. I’m not even talking about the maturation required to get to the point where you’d consider all of this.

The big problem is whether or not the vendors you work with have bothered to make their APIs capable of doing anything useful.

Does your phishing email software have an API that allows you to pull the details into your ticketing system and close it off there? Do you have consistent firewalls across your environment so you know what websites are being visited? Can you remotely control your EDR software to pull a standard package of data from these systems? Can you also get the malware from said system to then automatically push into the sandbox?

I’ve run across many, many barriers where trying to get 30% of the way is impossible because the vendor has assumed you only want to use the user interface they provide. The useful functions required just don’t exist in a public API and any attempt to circumvent this by reverse engineer any other API or directly accessing an internal database violates the support agreement–I am trying my best to avoid naming a vendor here.

Accepting your fate

So what do you do in this scenario? Don’t use the SPG approach and just accept the reality that you will work to reduce the windows needed but only where practical. Options beyond that may include finding better vendors to work with too.

If you have a vendor promising you an automation tool that will give you that single pane of glass, press on them hard and maybe reconsider any future relationship with them because it’s again a fool’s errand and a waste of time.

-

How I got my anime fansubs before the Internet

This is a repost from a Twitter thread I made back in September 2017.

So on a Slack I am on, I ended up talking about how fan-subtitled (fansub) anime distribution used to work in the 90s.

Anime would cost between $15 and $30 USD commercially depending if it was subbed or dubbed – $25-50 today.

However, LaserDiscs from Japan were super expensive. You’d have to order them via mail or phone and they’d be $300+ sometimes plus shipping.

In some cases, one LD collection would just have 4 episodes and cost that much. You’d be looking at $80-$100 an episode in mid-90s money. These discs would typically be not available to purchase until 8-12 months after the show had aired–unlike Crunchyroll’s 1-hour!

Fansubbers would buy these discs with their own money. Sometimes donations would be taken but typically it was out of pocket.

Typically the fansubbers would just stop distribution if the anime series was picked up by a distributor in the market they’re in.

Fansubbers would spend late nights–whole weekends too–just going over the show, watching it endlessly, translating and timing a script.

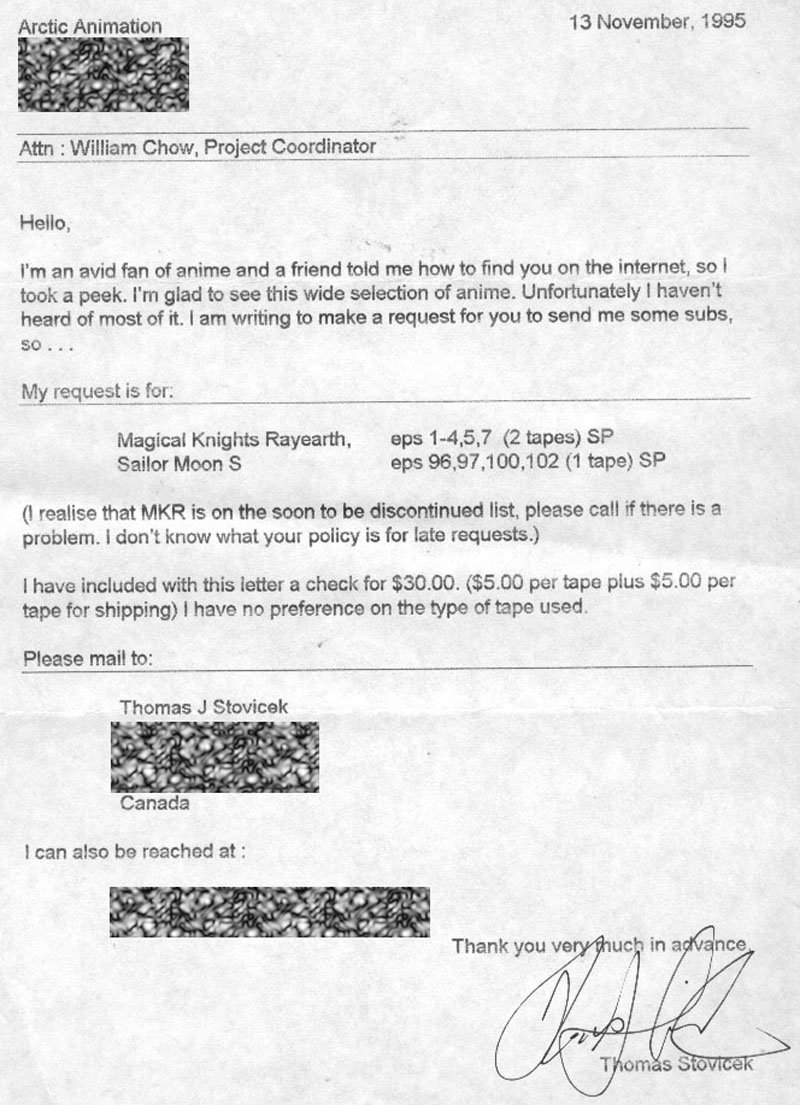

It was tireless work. I had friends at Arctic Animation who did all sorts of great shows like MKR and Akazukin Chacha to name a few

Once translated and timed, you’d eventually feed the script into a computer and then use some fancy hardware to overlay the subtitles. It was a 1:1 copy by the way. There was no way to speed up the process. Play from LD, record to VHS or SVHS. Found a mistake as you watched the subtitle? Welp you’re out of luck! You’re going to have to fix the script and then restart!

SVHS was used to keep the quality high but it only really benefited the subtitles, not the video since the LD was not able to output SVideo. You’d usually copy the SVHS “master” to other copies for use for distribution. I hate the term “master” and will only use it once.

Once you’ve gotten your copies, you’re able to distribute the tapes assuming that nobody bought the rights in the three months it took.

So now you want a copy of MKR? Well it is time to send a letter and a VHS tape or a few off to your favourite fansubber! You’d be waiting however long it would take to get your copy. Arctic was here in Vancouver so I’d just take a train to get my copies.

Some fansubbers went overboard with their methods. Here is how VKLL did theirs. I had these copies at one point.

VHS distribution died when it became effective using the Internet to distribute copies in DivX or even RealMedia format. It was around the time that anime got super popular and anime cons were just popping up everywhere.

I cannot remember Arctic’s last release, but it was definitely in the early 2000s.

Nonetheless, it was interesting to see the shift from VHS to digital distribution for fansubs and the rapid turnaround it got. You’d see fansub groups in the mid-2000s pumping out subtitled copies in a matter of hours after airtime. However, unlike when LDs were used, no money is going to the right holders in Japan for these shows.

These days fansubbing is a lot less prevalent. Crunchyroll has the market cornered with its 1-hour after broadcast release schedule.

But yeah! Subs not dubs.

-

Hi-Vision and anime

This is a repost from a Twitter thread I made back in July 2019. I will be resurfacing old threads I happen to like from time to time to make them available on cohost too!

So I’m stuck at home a lot these days and someone had posted about having watched Patlabor the Movie yesterday, leading me to be inspired to watch the sequel.

It happens to be a favourite of mine, but I discovered something rather neat about this alternate reality.

Hi-Vision!

Just bear in mind, I may spoil some parts of this movie inadvertently so I am going to do my best to keep this spoiler-free if you somehow haven’t seen this movie.

I will deviate from Hi-Vision talk because the retro-futurism in this movie is just so cool.

This movie was released in 1993, about four years after the first movie, which is equally good. Two years prior, Hi-Vision (MUSE) became commercially available.

You can read more about this format here.

But yeah. HD video that was analogue!

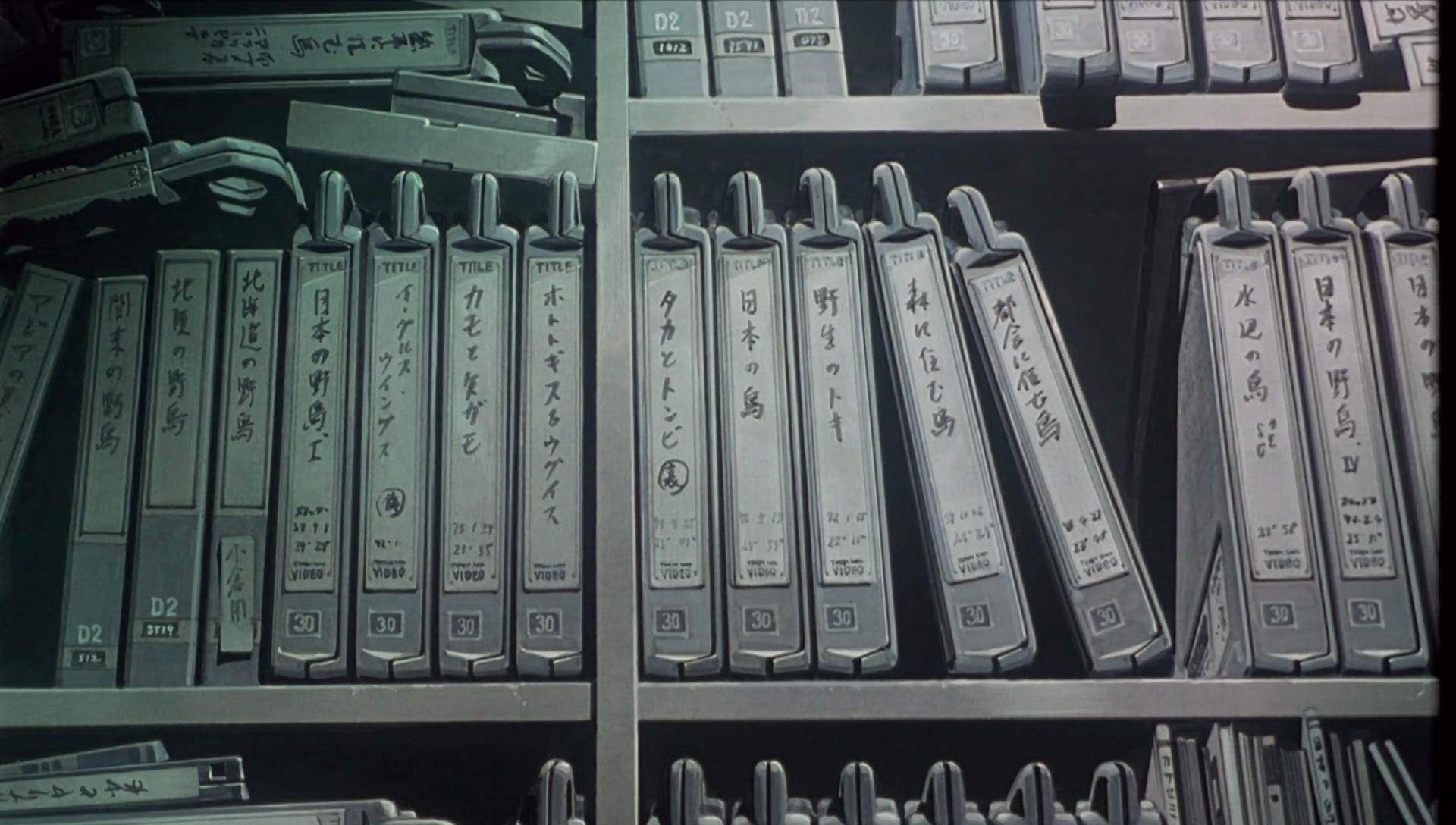

We didn’t end up with LaserDiscs in this movie although I guess for the sake of this thread I’ll show the use of compact disc-like media, but we did get to see VHS tapes everywhere.

And yes. There are TWO HD formats for VHS: W-VHS and D-Theater.

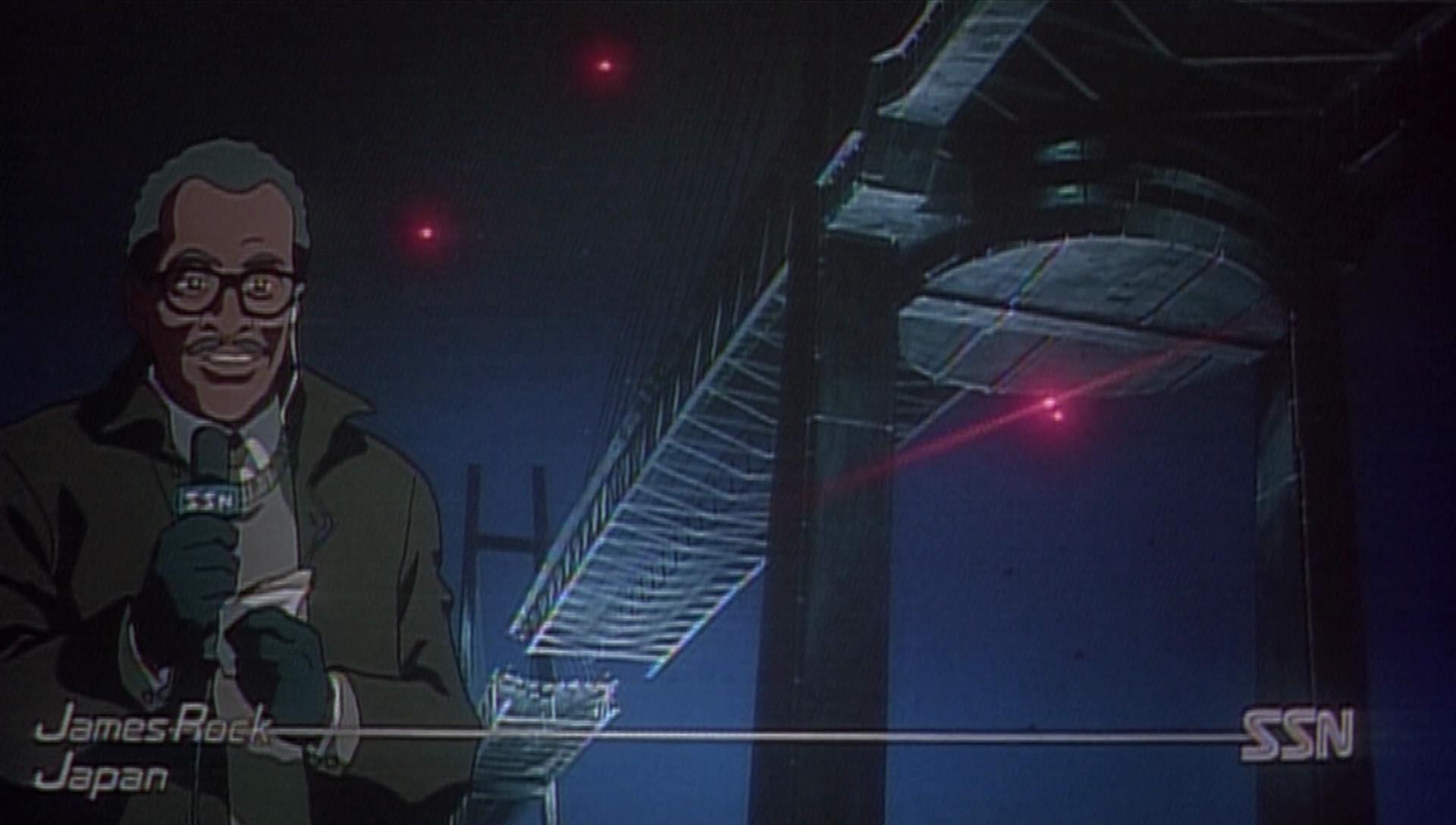

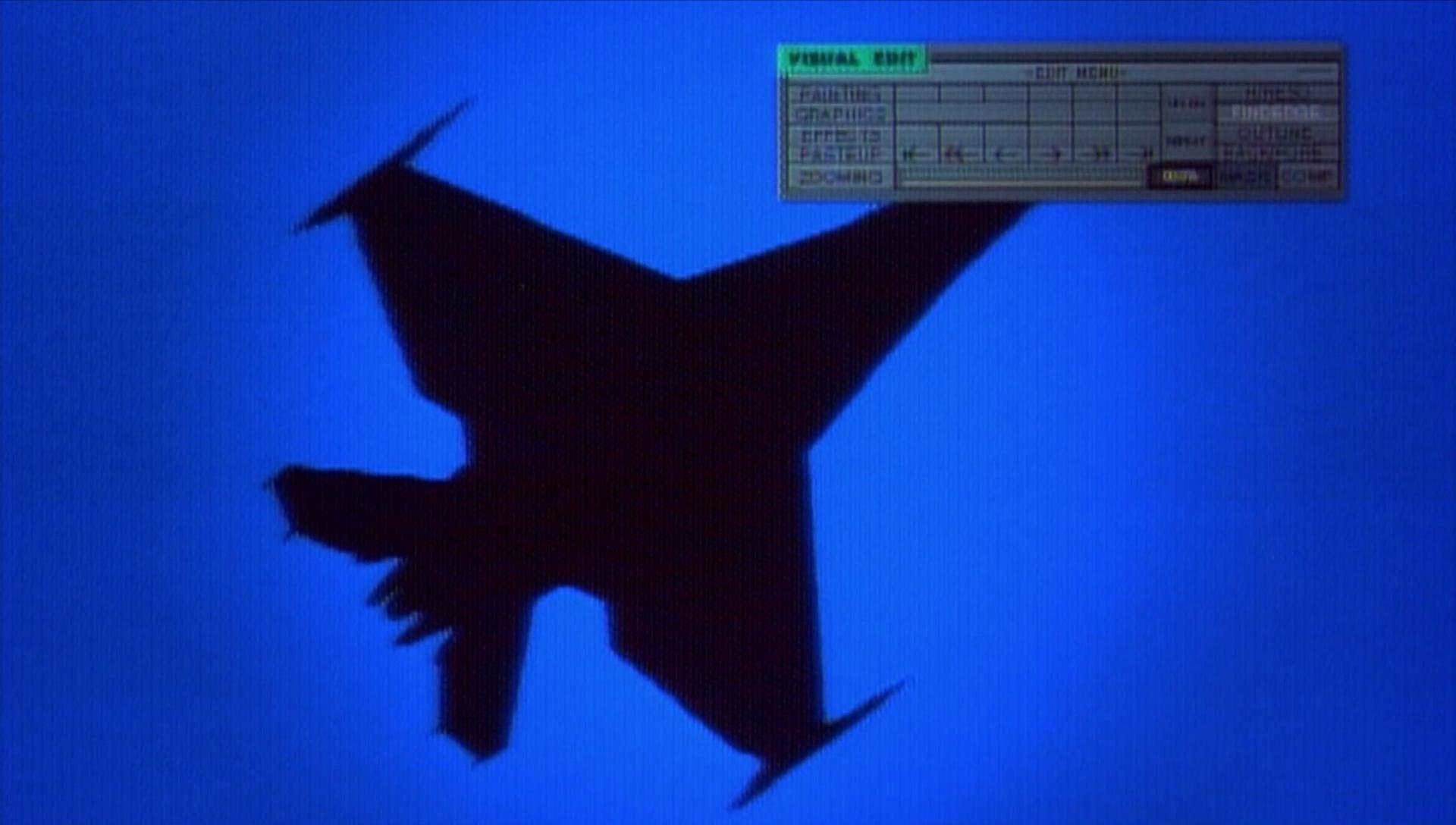

So where does Patlabor 2 come in? Well we start off with the bombing of a bridge in Tokyo via a fighter jet supposedly belonging to the JDF, which sparked a political crisis and confusion throughout the Japanese government.

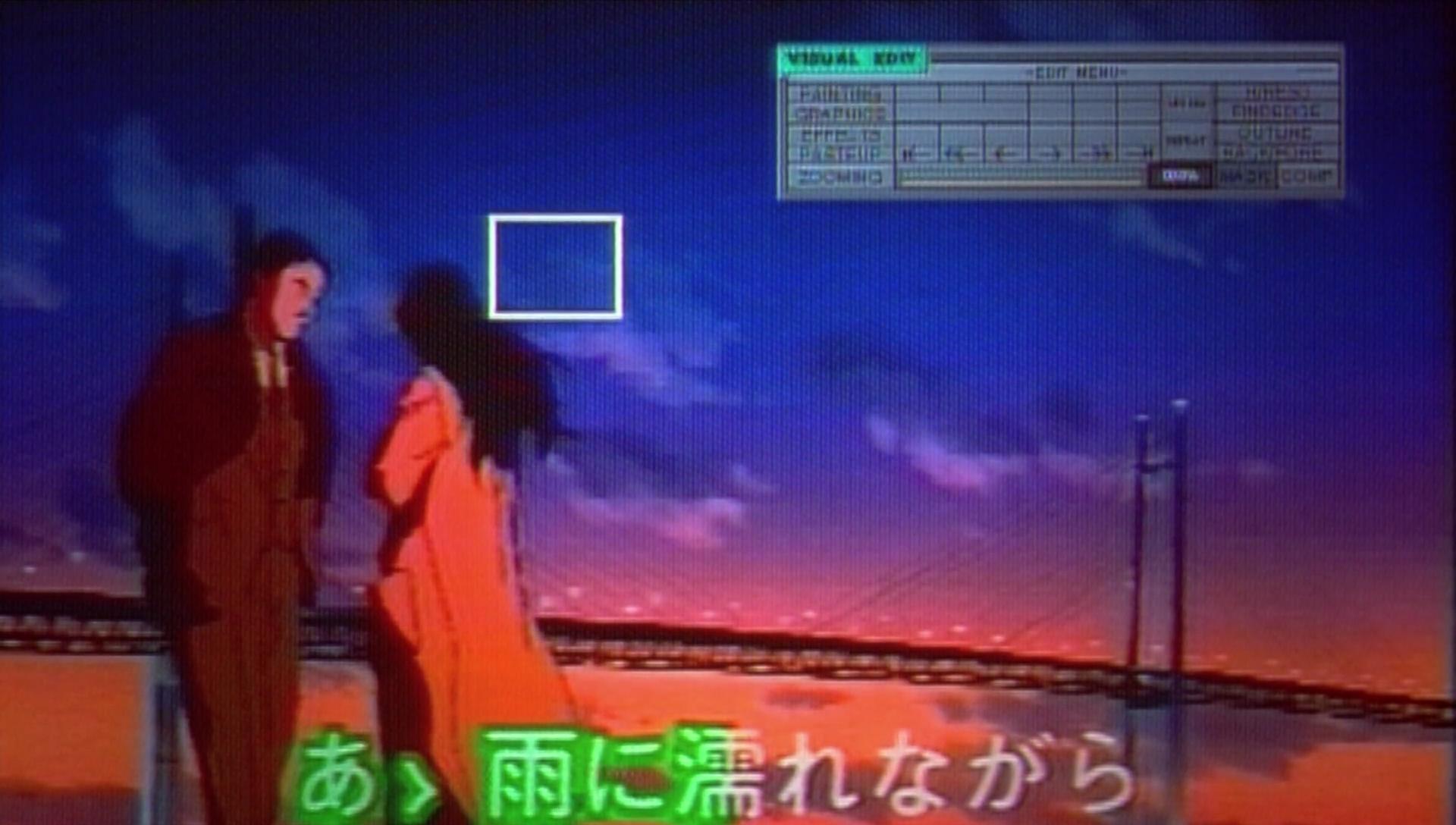

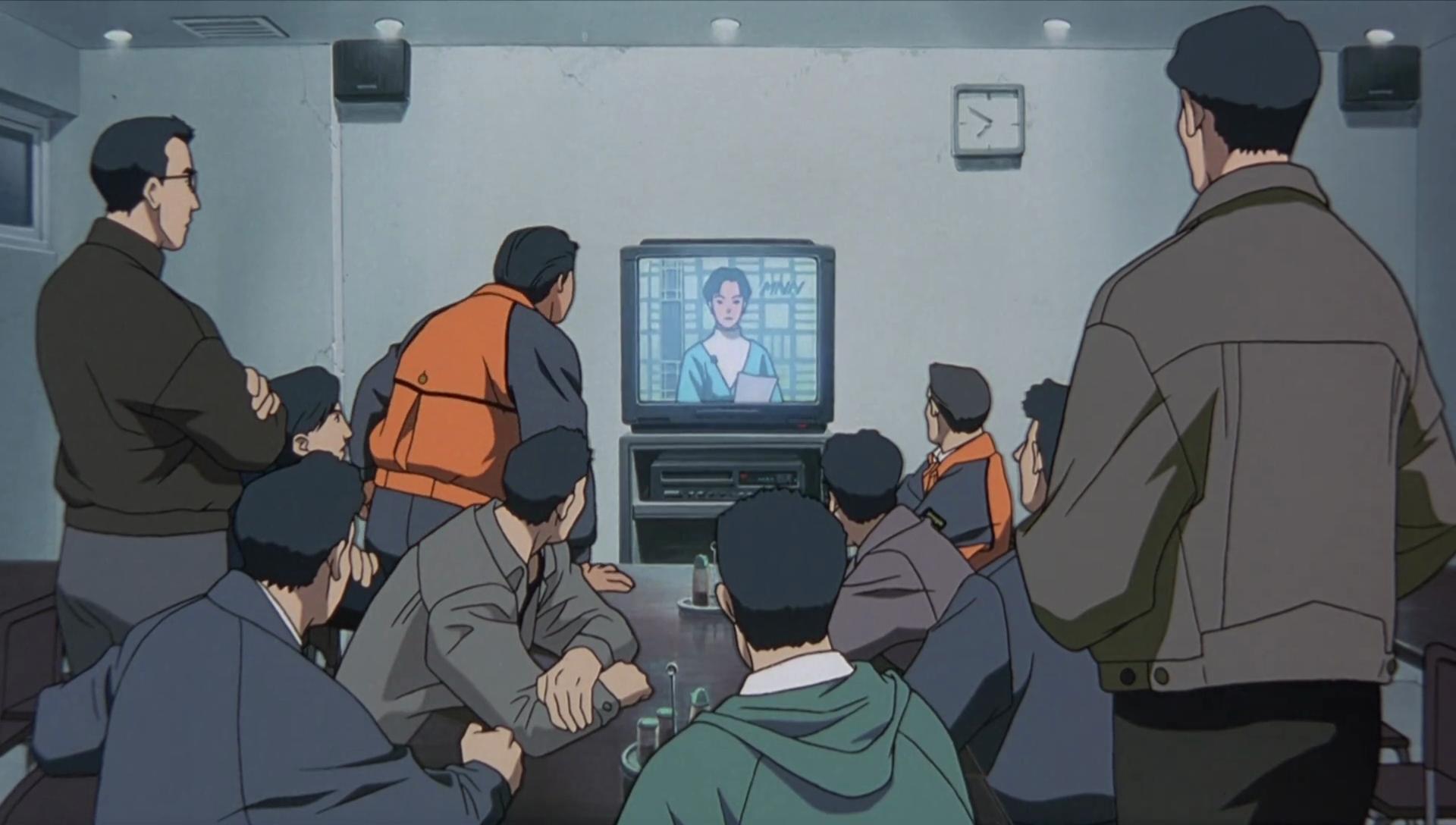

TV broadcasts were in 16:9!

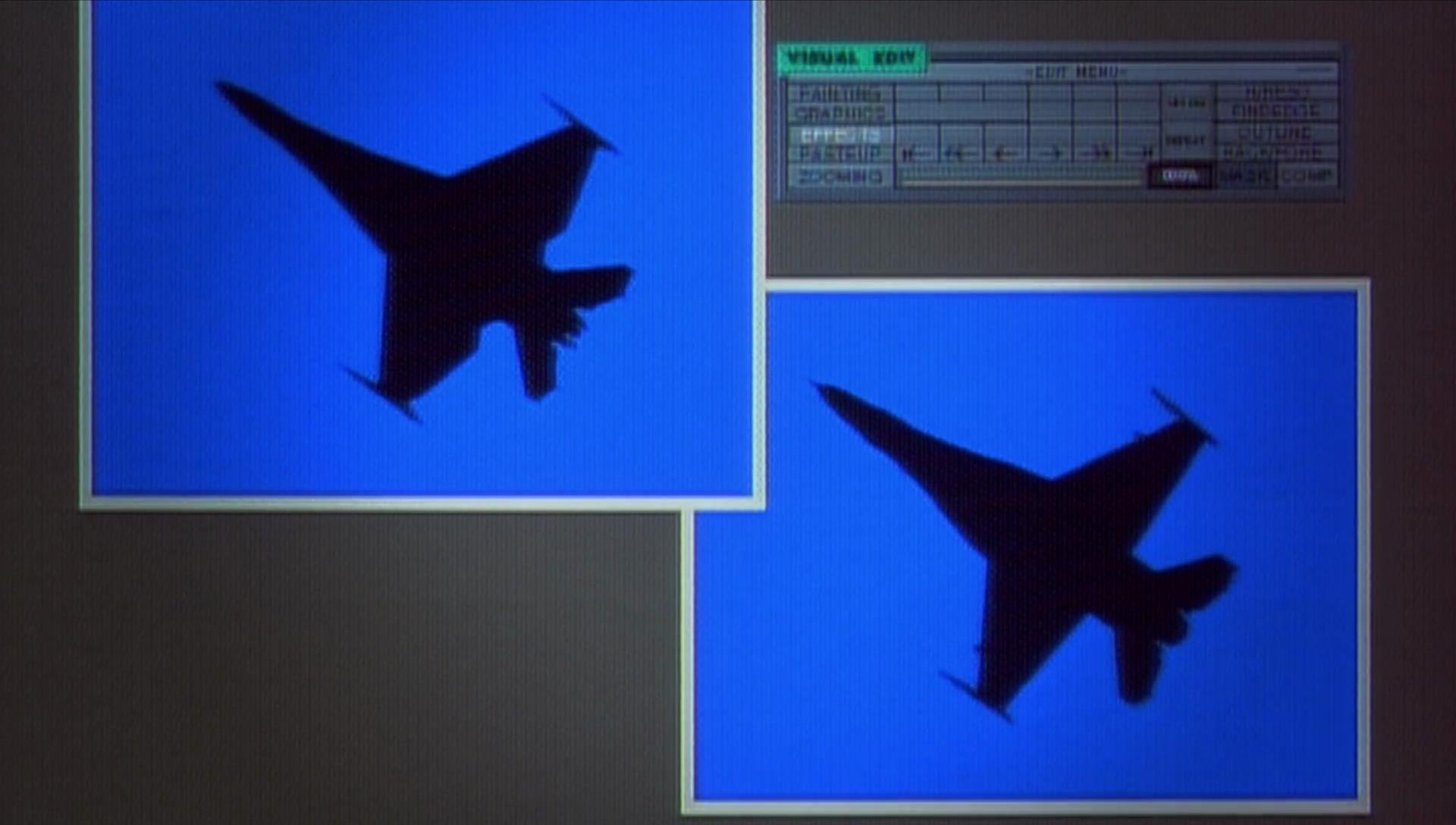

Eventually video of the incident from the ground is revealed and it “proves” that the bridge was bombed by an F-16 variant owned by the JDF.

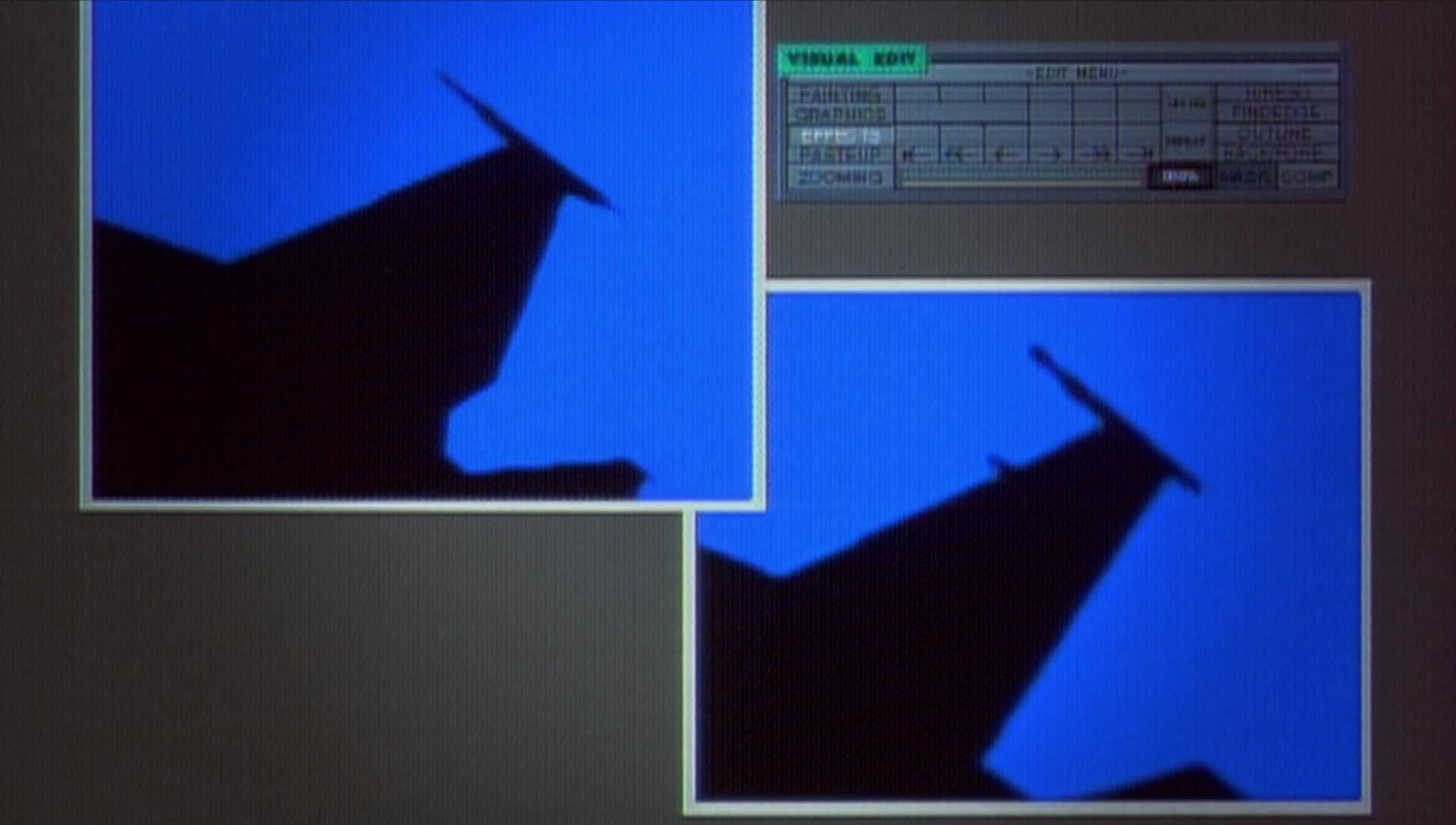

Because of it being an HD video, they were able to “enhance” the image to demonstrate that the bridge was attacked by missile.

You couldn’t get this resolution with your standard Handicam or whatever from back in the day because it was 480i. You could simply not zoom in like this; and while questionable for this 1035i source, it’s a lot more plausible.

Naturally recording this was for a karaoke video.

Eventually the police division centred in this movie comes into investigate and visits the videographer who had the master recording, but finds out that it was taken by “another officer”.

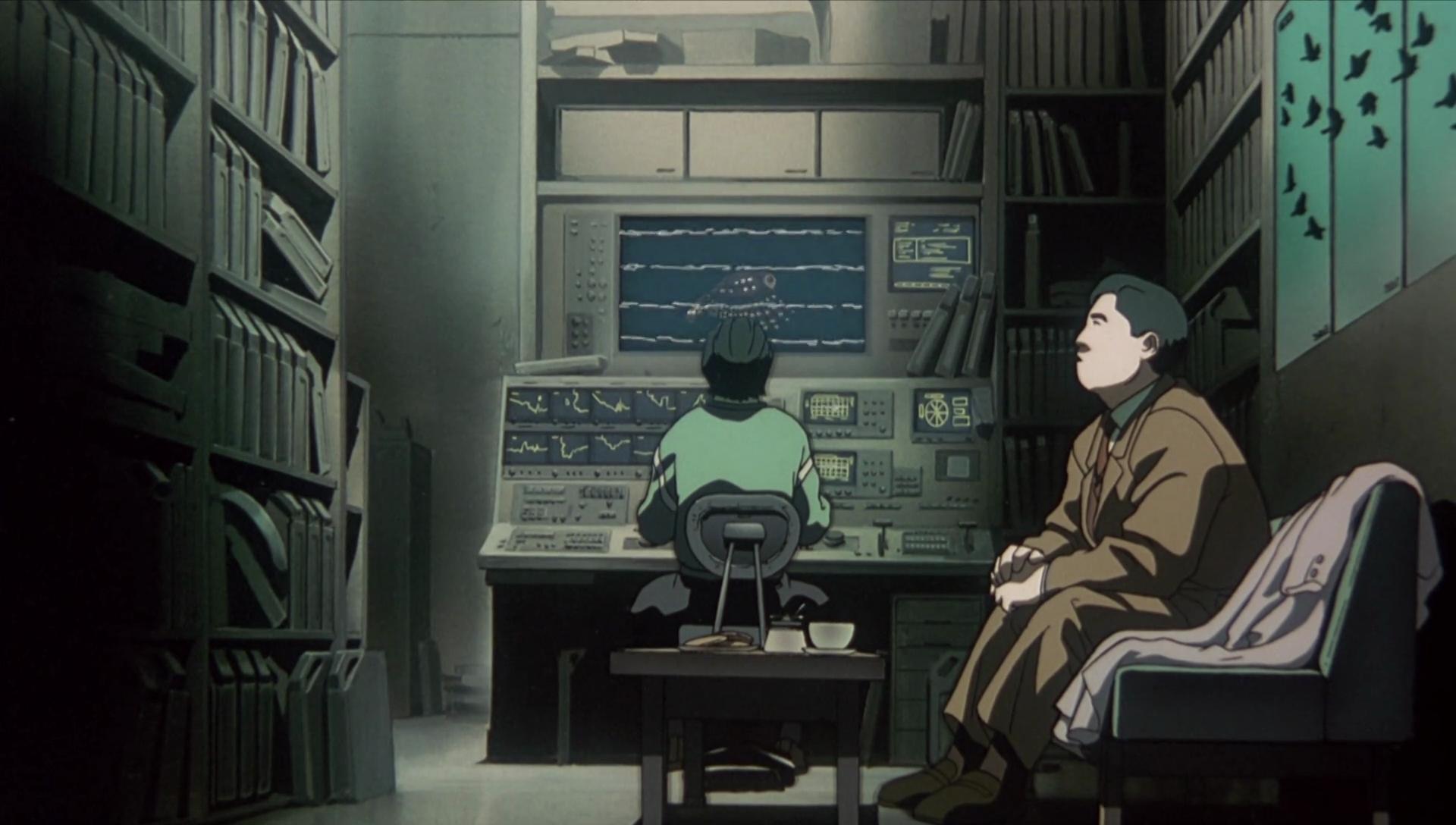

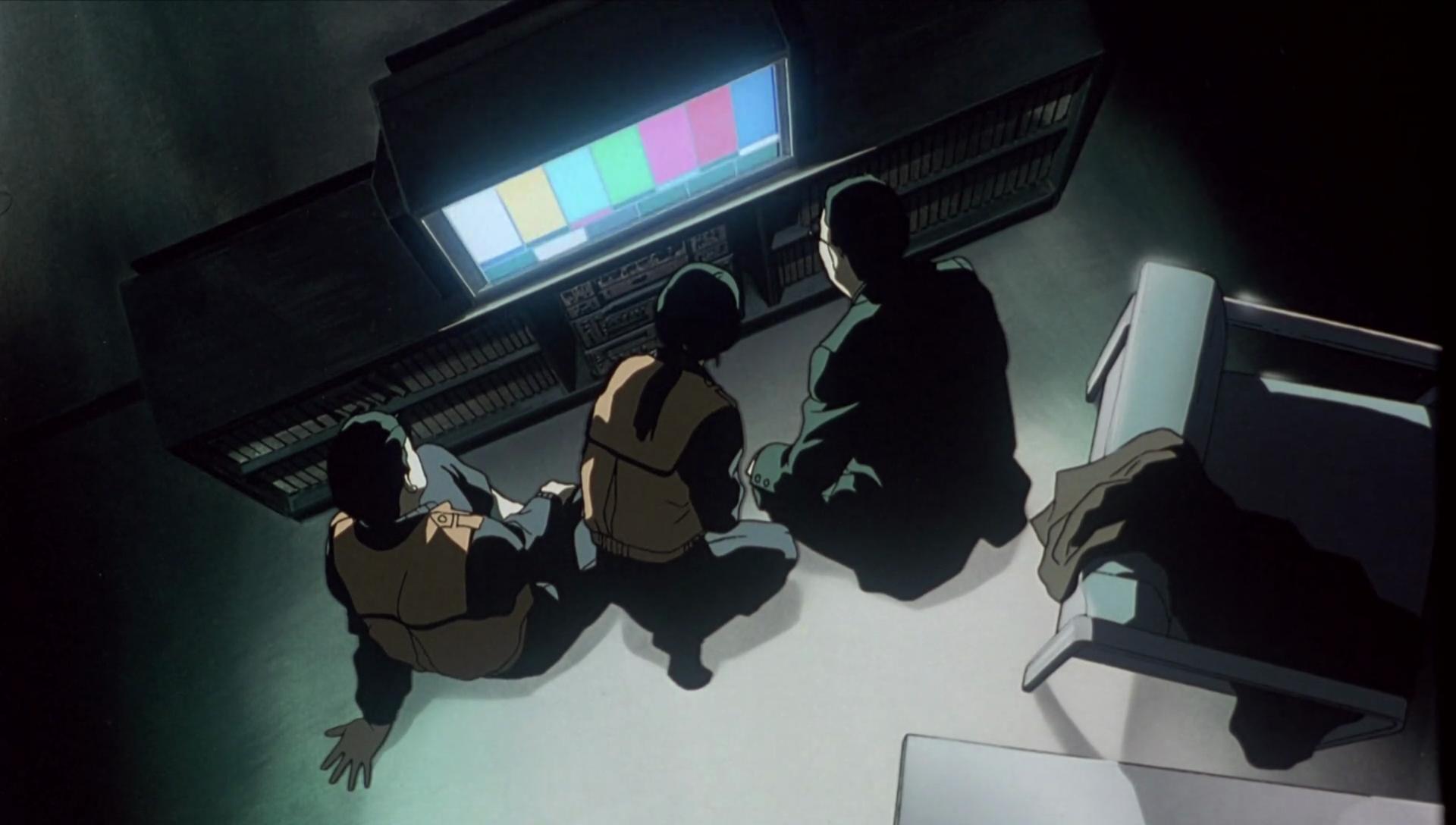

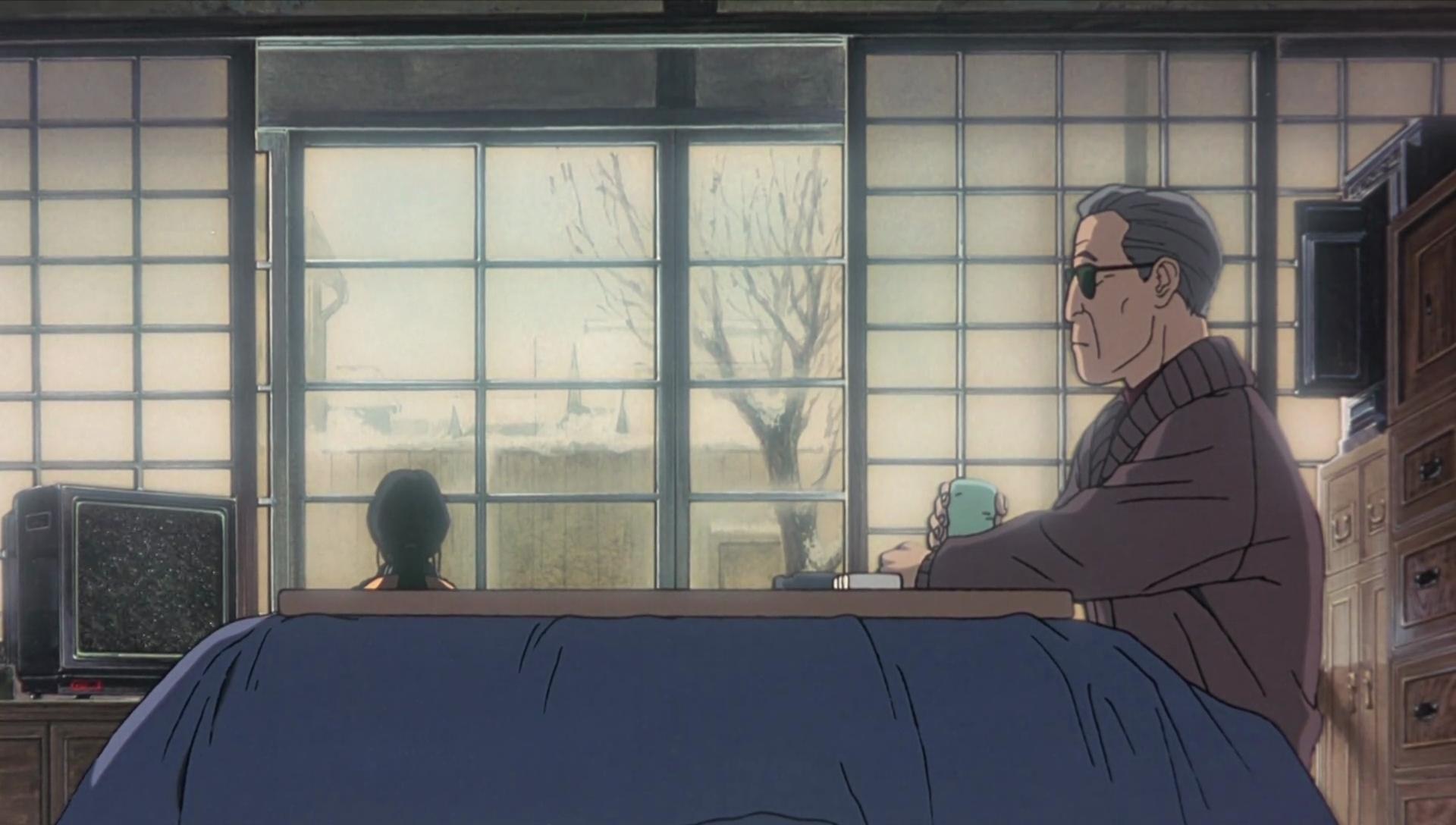

However, take a look at all of the recording equipment that this videographer has; 16:9!

We quickly go to another scene where the “other officer” ends up being a JDF [spy] of sorts. He wants to show the tape to the police division.

He finds himself befuddled with this whole VHS setup. Look at the three players with weird buttons for tape length and cable inputs.

Just look at all of those sweet buttons and very 1990s setup. We have a 16:9 CRT TV in what is a 1999 setting for a movie made in 1993.

And again, it’s for karaoke.

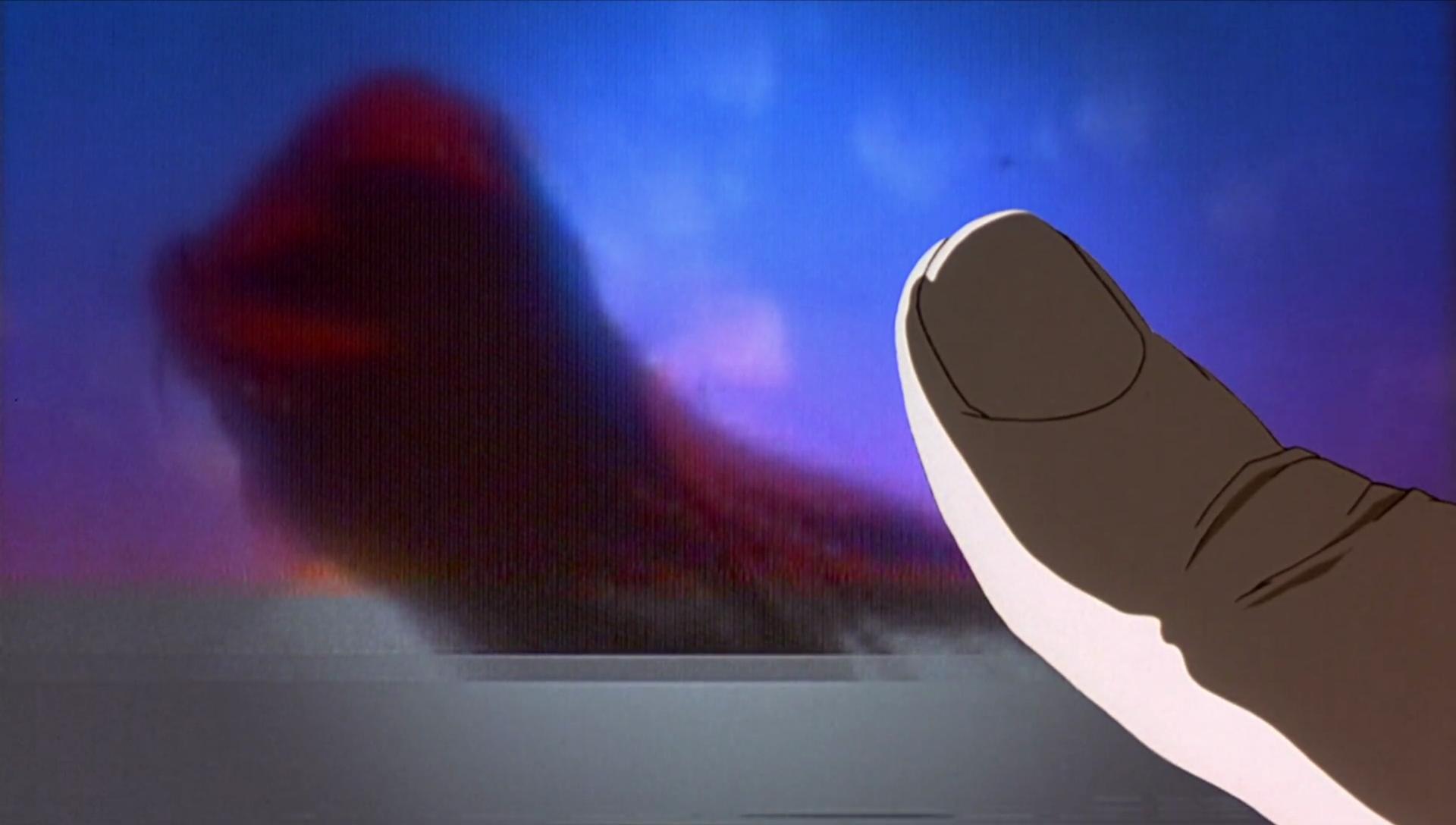

So of course, we find a “speck” in the video that demonstrates that there is something unusual. This of course was from a few minutes before the missile attack.

Somehow there is an editing setup either in the room they’re in or they make use of the computer room they have in the building–this is shown in the first film.

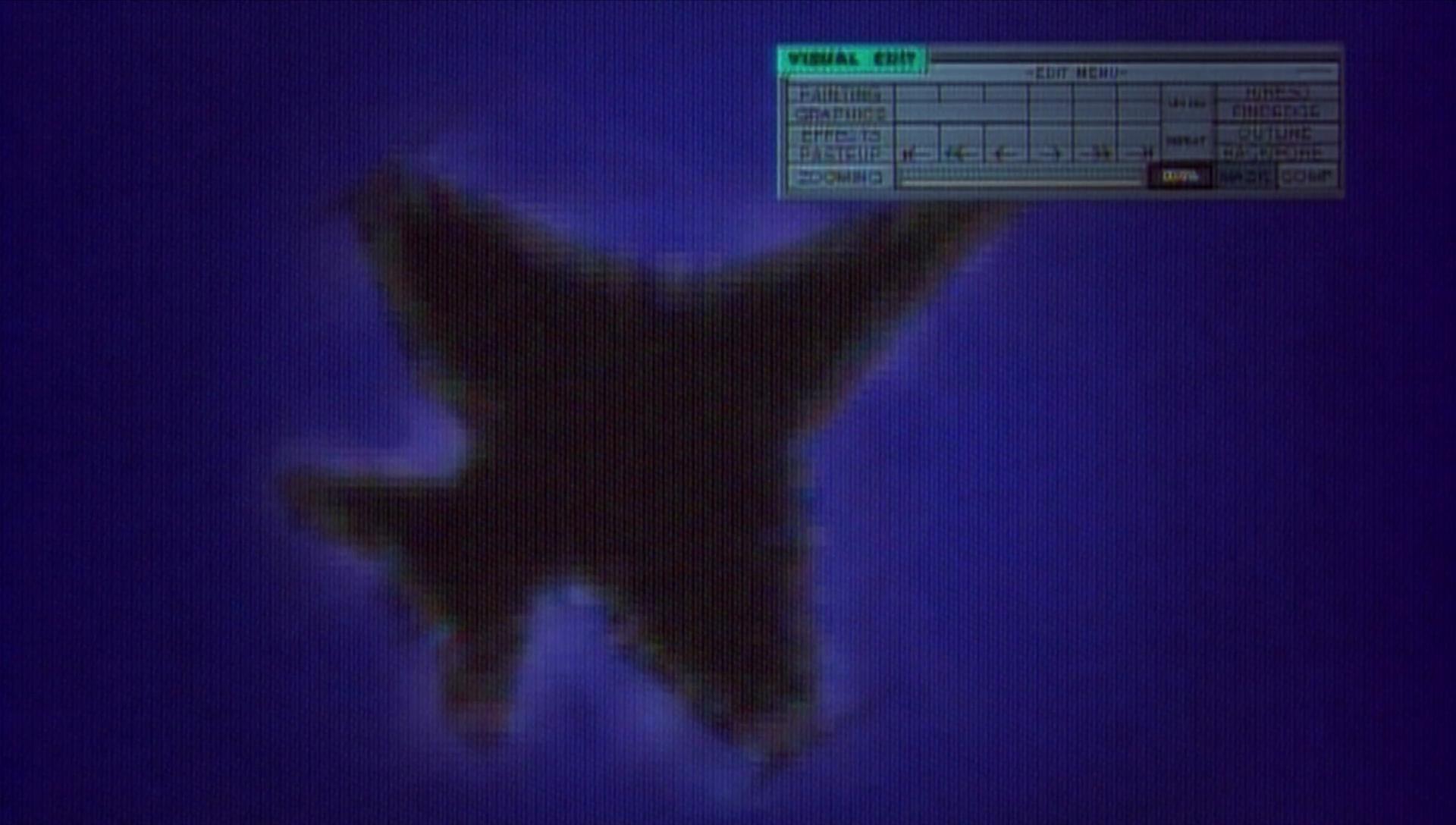

Let’s enhance the image everybody! Oh look. It’s the fighter jet that attacked the bridge!

But wait. Here’s the twist: this is not the plane we saw in the news broadcasts. The news said this was an F-16J, but this appears to be another variant that has stealth and exhaust nozzle the JDF doesn’t use!

What is going on here?!?

Anyway, the tape becomes the catalyst for things going very awry within Japan and we start to see martial law being implemented in order to curb the possibility of a civil war.

The scenes make me think of the October Crisis from the 1970s here in Canada.

Not everything is 16:9 in the movie as we do see computer displays with 4:3 ratios instead.

Bonus optical media snapshot. I really, really love the aesthetic of optical media use in old anime.

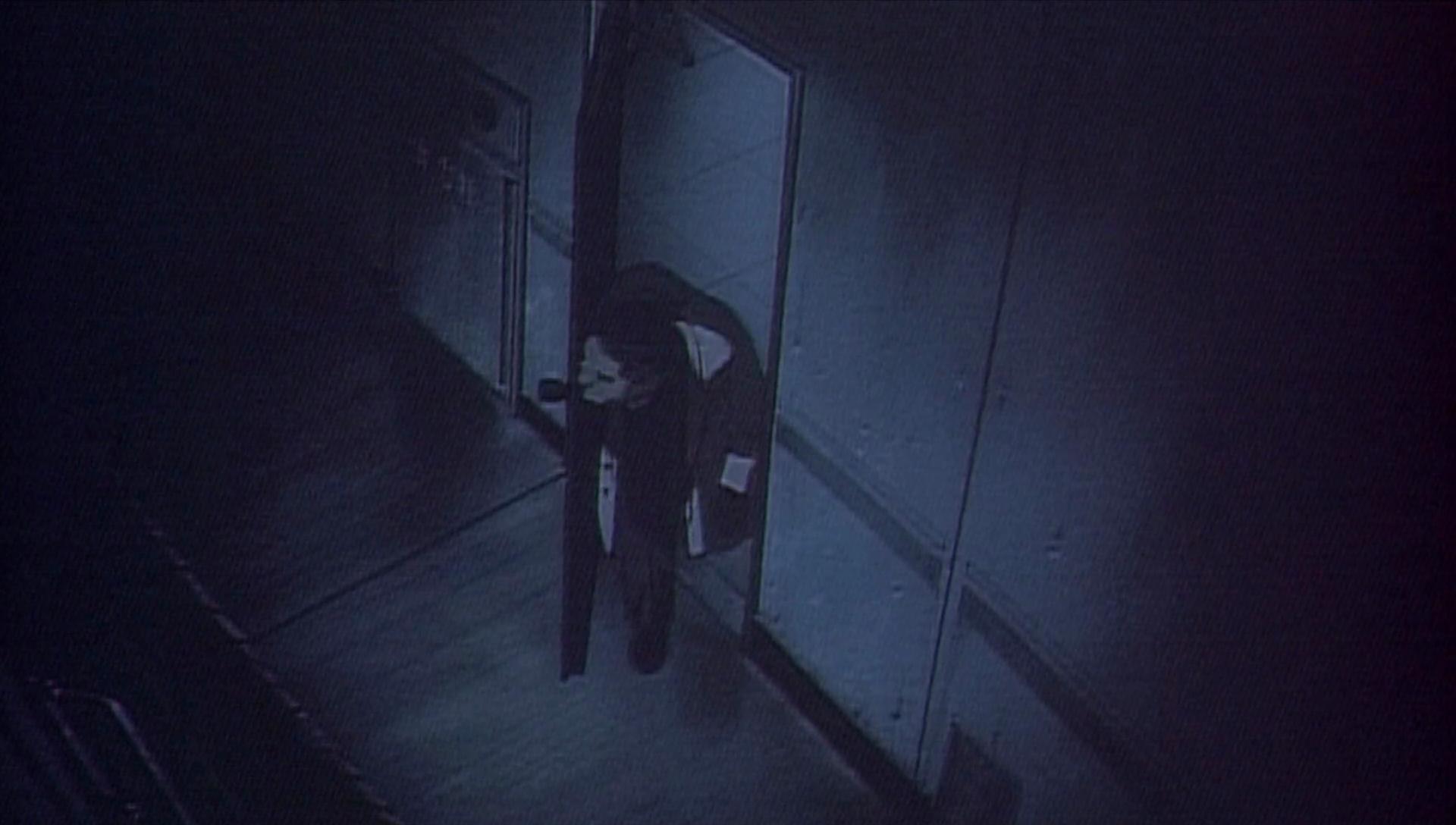

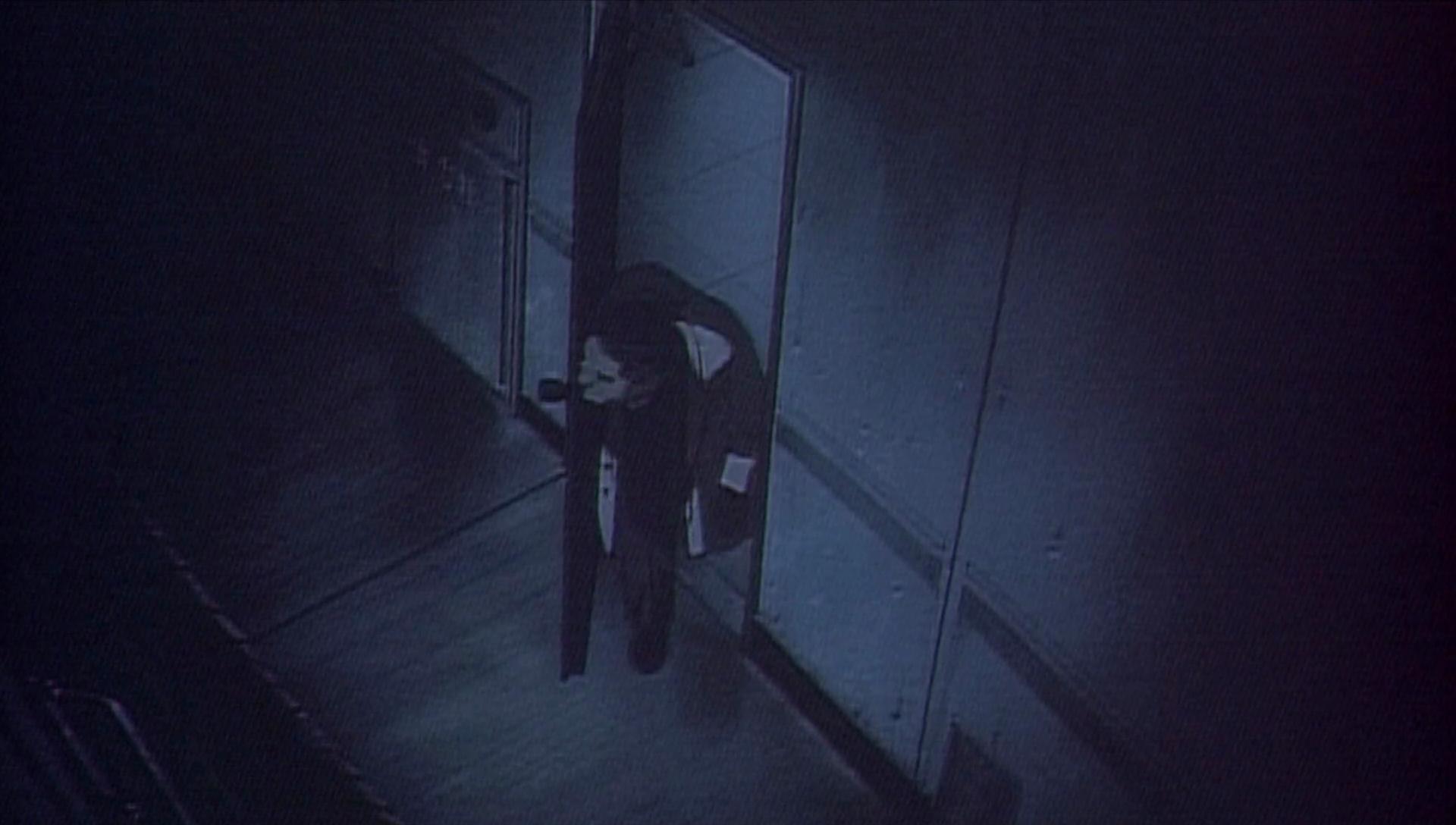

Even CCTV setups were using 16:9 aspect ratios. This is a really wild world because it has only been in the past ten years that we’ve seen this with security cameras.

This is a scene where two of the characters were watching a detective snoop about.

There’s a lot of mobile phone use in this movie too, but interestingly the use of landlines still seems popular enough to advertise what appears to be long distance services from KDDI’s predecessor, Kokusai Denshin Denwa.

Make a call to Hawaii I guess?

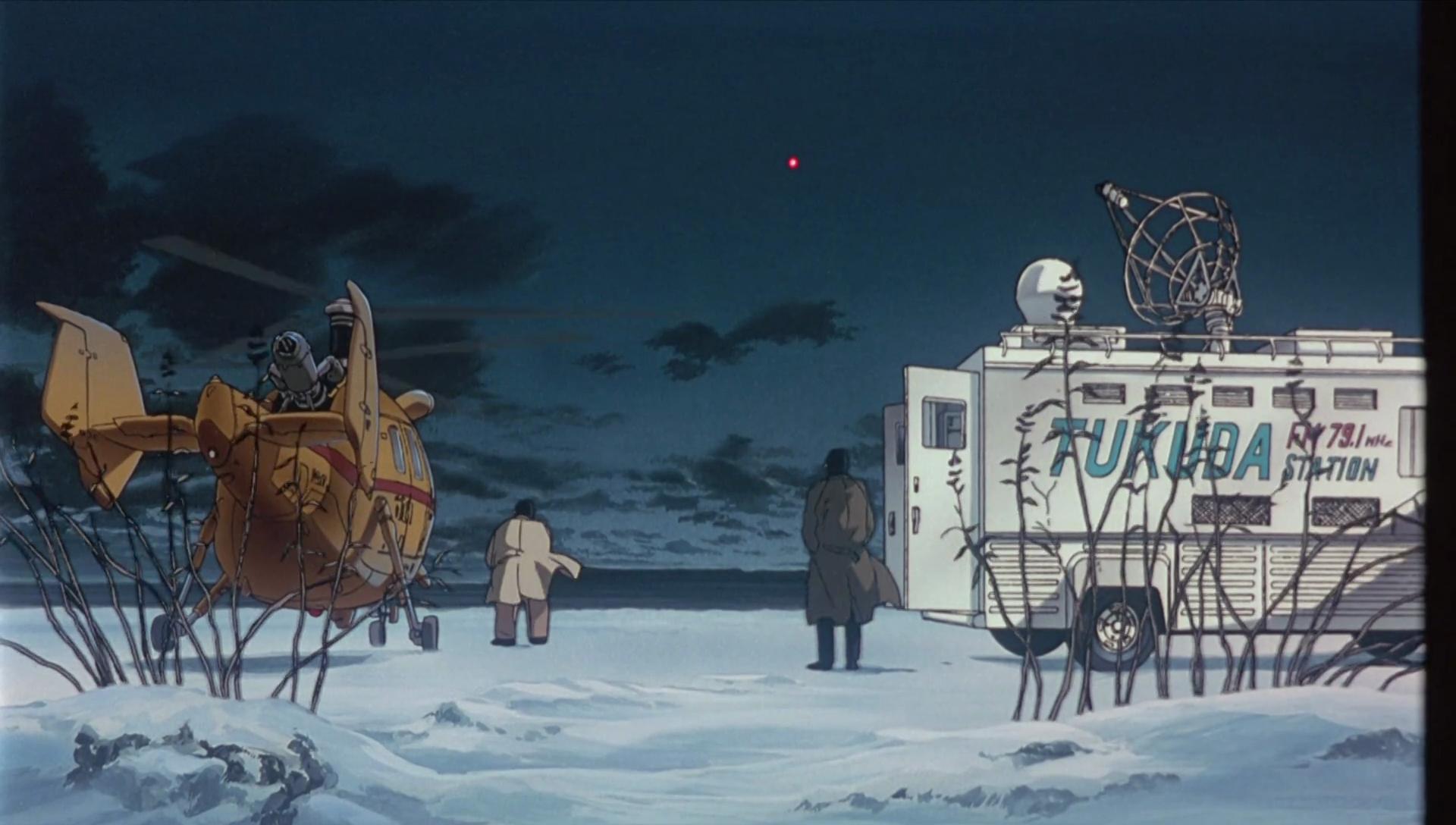

Even a radio station appears. This is a valid frequency although it appears that it didn’t exist until 1996.

Anyway, Hi-Vision is explicitly mentioned in this movie and I really like the idea that somehow in the early 1990s, analogue HD video started to take off and this movie made it core to the story.

Plus it had cool mechs.

This movie is super fun to watch but it gets more interesting if you have a good understanding of contemporary Japanese politics at least in the 1990s. Knowing how Article 9 of the constitution affects Japan as a whole is really something you should consider before watching.