SkyTrain and Industrial Control

This is a Twitter thread from July 2018 that I made into a blog entry.

I want to talk about how important industrial control is and why the general public is woefully unaware of how they interact with it on a daily basis.

This is a post on SkyTrain, Vancouver’s rapid transit system and how safe it is until users circumvent it.

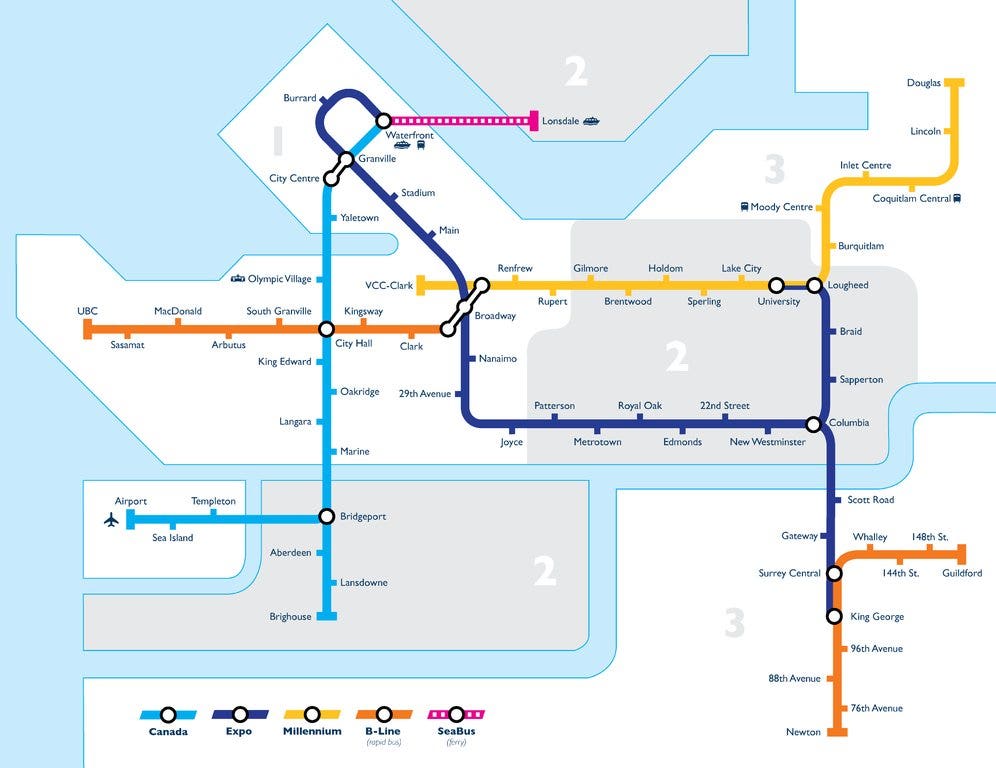

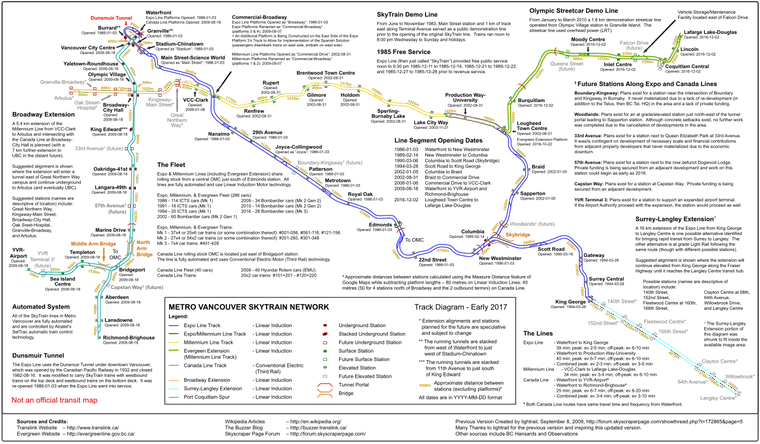

SkyTrain has just about 80 KM of track and it’s 100% automated. This means that when you walk on to any of the trains on any of the three lines, there is no driver. Because of this, it can achieve and has achieved 70 sec headings, meaning you don’t have to wait long for a train.

More often than not it’s about 120 sec but still few systems in the world can achieve this maximum frequency.

Its frequency is also its biggest Achilles heel when things go awry, but I’ll touch on that shortly.

For the very curious, the trains use the Seltrac moving block system. This allows for the trains to run very close together to the point where trains can actually be right in front of each other with a few metres to spare.

To prevent people from going into the tracks, there are various sensors at entry points where humans could interact with the trains. The trains don’t have anything to detect a human is in its path; it just knows where it is.

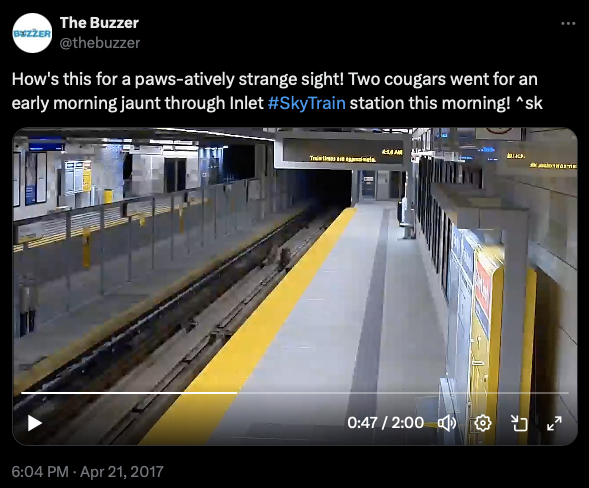

Or in some cases wildlife gets into the track. This is a new extension of the system and it’s not too far from an interface zone, allowing for cougars to enter. The line was not operating at the time.

So optimally, trains know where they are and humans never enter the track. Unfortunately, it does break from time to time…

(View talk on elevator security on YouTube)

The way I look at our rapid transit system is like this: it’s like an elevator. An elevator is designed to never kill you provided that you don’t circumvent the safety controls.

So what happens when humans circumvent the safety controls by opening doors when the trains are stopped? A lot of things and it messes up the balance of the system.

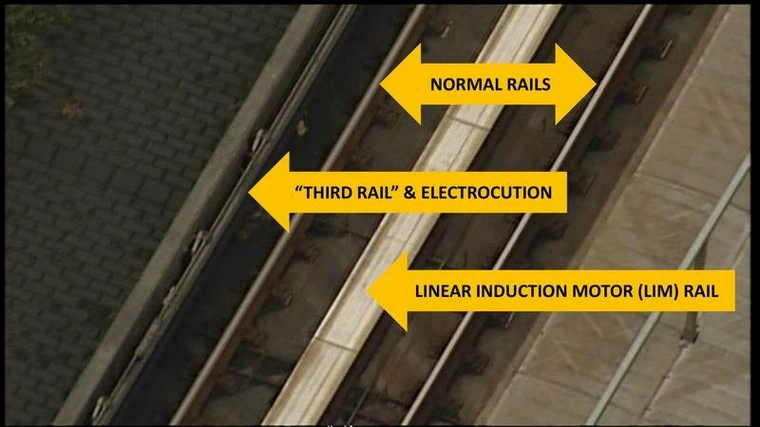

SkyTrain operates using a third-rail system, meaning that electricity is provided by a rail on either side of the track to feed electricity. It is very easy to end up touching it if you are unaware.

Also the trains operate at 80 KM/h at maximum speed.

All of this means that if someone exits a stopped train, everything starts to go hairy fast.

First off, SkyTrain has to have the section of track where people are thought to be walking through turned off and to stop all trains from approaching the stations between them. This means that a huge section of track going both ways is now disabled.

Secondly, attendants have to assist the riders who opted to leave the trains with getting on to the platforms. This has to be completed before we can do anything further. It may take an hour or more.

So here’s where the fun part comes in: what happens when you decide to knock out power to these trains? We lose the ability to trust their state.

That’s right. We’ve lost the trains and now the system has no idea where any of them are.

To bring the trains back to life we cannot just turn them on and tell them to go to the next station. They themselves do not know where they are and the system does not have the ability to make them trust their current position.

These self-driving trains however have to meet requirements every few months by having them driven by an operator. Almost all attendants are trained to operate the train when need be–due to weather or maintenance.

So to fix this: we have to have the train sets driven into their nearest station one set at a time. This is the longest part because there are sections of track that are nearly 3 KM long.

Once this is done and we’ve ensured that nobody is in harm’s way, we can have the system come back to life.

I’ve ridden this network every working day for the past decade and can [confidently] say that the system is very safe. However, the biggest problem it has is that when it breaks, people tend to get frustrated and cause the system to break further.

In 2017, the system recorded a record 151 mn passengers (compared to 117 mn in 2010) and on average the majority of system delays are caused by humans interacting with the trains either intentionally or unintentionally–I will not elaborate further.

(There is a train 069 BTW)

How this all ties into industrial control [(IC)] of course is that this is the very definition of one that the public uses every day and pays no attention to how it works. Often we talk about IC in power plants, natural resources, and elsewhere, but our mass transit systems are IC!

IC security is super important but it is also important to understand how much goes into making a good IC system work. It isn’t just having to worry about security matters but to also plan for humans interfering with the operations of things.

So the next time you’re stuck on a train, don’t break the emergency seal. It may be 15 minutes for you but you may cause 120 minutes for others.

I should add: I don’t work for TransLink! If I did I’d probably wouldn’t be allowed to [chost] about this stuff. I work for a company that heavily uses industrial control so as a result I have an interest in how things like SkyTrain works!

Fun fact: I was DM’d by two TransLink employees asking me if I worked for them when this thread started to make the rounds locally. I literally just transposed my knowledge of industrial control to how these trains work! Knowledge of industrial control equipment is just something I gained from my career and it isn’t hard for me to look at systems and figure out how they tick.